Those struggling to get a foothold in the ever more competitive world of journalism can take solace from the story of BBC Panorama reporter Raphael Rowe.

In 1988, 19-year-old Rowe, alongside Michael Davis and Randolph Johnson, was convicted of the murder of Peter Hurburgh. The trio, dubbed the ‘M25 Three’ in the press, were sentenced to life in prison.

Twelve years later, in the face of overwhelming evidence in his favour, Rowe was acquitted. A free man at last, he diverted his energies into securing justice for others as an investigative journalist.

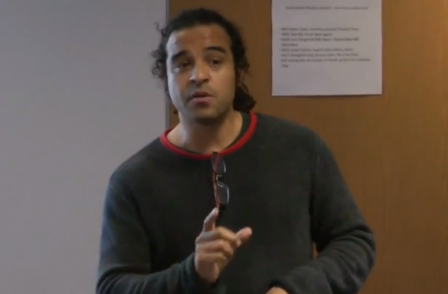

Addressing journalism students at City University in London earlier this year Rowe spoke candidly about his ordeal and the long road to redemption.

“At 19 years old I despaired, finding myself in a secure unit at Brixton prison, never to be released,” he recalls. “I was a volatile, angry convict – accused of something I didn’t do, I couldn’t understand what was happening to me. I was helpless and spent a lot of time in isolation from other inmates”.

Rowe campaigned vehemently in these early years to have his conviction overturned, but to no avail.

“I was campaigning relentlessly. In 1993 there was an appeal, but it was rejected when I was sure of success. “It was heartbreaking but I couldn’t give up while I knew that one day, justice might be done.”

Then, at the age of 26, Rowe encountered several other wrongly convicted prisoners who would be instrumental in his development as a journalist and campaigner.

One was Patrick Hill of the ‘Birmingham Six’, acquitted in 1991 of involvement in two pub bombings in 1974.

“Paddy was very good to me,” Rowe said. “I remember him telling me, ‘If you don’t fight this injustice in the right way, you’re never going to be released’.”

“The ‘right way’ meant understanding how to use my anger and energy in a productive manner. I realised I needed to focus on the media if I was ever going to get out.

“I understood what a significant role the press had played in my conviction. The way the national papers vilified and demonised me and my co-defendants influenced the eventual decision, I have no doubt about that.”

Deciding how he could use the power of the press to his advantage became Rowe’s primary focus. In the seventh year of his imprisonment he embarked on a correspondence course and educated himself on the intricacies of the criminal justice system.

“I committed myself to understanding how journalists work, because I desperately needed them on side. I needed them to tell people outside prison that I was innocent, it was my only hope. The legal system had failed me, but I was convinced the media could make things right”.

Rowe’s progress was inhibited by sporadic transfers between some of Britain’s most toughest jails. “I was moved between Wormwood Scrubs, Pentonville, Brixton, Holloway and others during those years. I crossed paths with some of the most dangerous men in the country and came through unscathed.

“Every time I was moved from a prison all my notes were left behind, which made finishing my course almost impossible.”

At the age of 30, Rowe was still languishing in a secluded cell struggling to make his voice heard. But renewed press interest in the case provided a faint light at the end of the tunnel.

“The attention from the media got the general public interested in the case again and started to rattle the cages of the judicial system, which is exactly what I needed.

“The nationals were on my side and new evidence meant it was starting to look like innocent men had been locked up, which of course was the truth. It was so encouraging, I dared to think the end of my sentence might be in sight.”

On 14 June 2000, 12 years after the original trial, the Appeal Court overturned Rowe’s conviction. While the judges were emphatic in their ruling, their hesitancy to officially declare Rowe innocent frustrated him deeply.

“I have battled every day of the last 12 years to prove I was set up by the police, to prove I am not a murderer,” Rowe told the media upon his release. “I still feel like I'm trying to make my voice heard”

Now a free man, Rowe focused on pursuing a career in journalism, which he had come to realise was his passion. “It was exciting for me, the idea that I could help people in a similar situation find justice”.

After a year travelling the world Rowe ended up chatting to Rod Liddle, then editor of the Today programme, during a tour of the BBC. Within minutes Liddle had offered him a job.

“Rod was a maverick who wanted to cause trouble more than anything,” he remembers.

“I think he wanted to hire me to outrage the Home Counties. But more importantly he saw my determination to pursue what I believed in, and that interested him.”

Rowe remembers his first day at the BBC with fondness: “I turned up in a suit – I’d never worn a suit before – not realising everyone else would be dressed casually. That was the first thing I really learnt, that I didn’t have to change myself to fit in.”

Rowe became a reporter for Today in 2002 and later worked on the Six O’clock News. He now presents regularly on Panorama.

Rowe has reported on a wide range of issues and played a significant role in the freeing of Barry George, imprisoned for the murder of broadcaster Jill Dando, with a series of documentaries in 2008.

“I am so proud about what I have achieved and I still value that obsession for truth as much as I ever did.

“When I recruit researchers now I look for those same skills that I had when I was starting out – sticking to what you believe in and never giving up.”

Rowe’s latest Panorama investigation, an investigation into illegal logging in the African rainforests, was broadcast last week.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog